Christian Wolff looks at the successes in testing and validation of metallised micro AM components for space and low earth orbit (LEO) applications

For years, the prospect of using metal-coated, 3D-printed polymer parts in space sat in that frustrating category of ‘promising, but unproven’. The upside was obvious. Dramatic mass reduction, design freedom that conventional machining cannot touch, and the ability to integrate RF functionality into compact, lightweight geometries. The obstacles were just as familiar. Could a coated polymer structure retain adhesion through extreme thermal cycling? Would it remain stable in vacuum without unacceptable outgassing? And how would the combined material system cope with long-term exposure to radiation and reactive species in the space environment, where very thin metallic layers can slowly erode or change their properties over time?

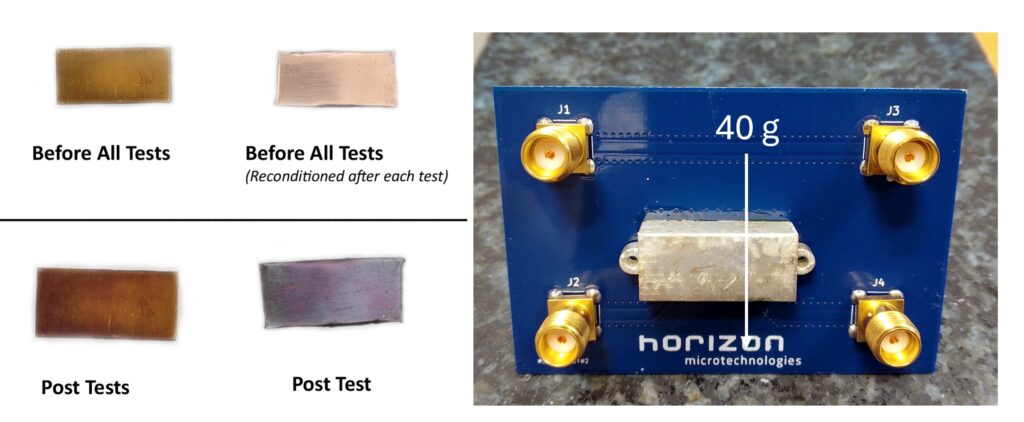

Over the past months, these questions have been systematically answered with data, not as a pure research exercise, but as a deliberate validation of a market-ready materials and component solution. We designed a structured testing and qualification campaign developed around representative demonstrators (including shielding housings and waveguides) with a clear goal of proving that our metallised polymer parts remain reliable under space-relevant stressors. Parts were assessed before and after the stress tests detailed below via

- Visual and microscopic inspection for damage (especially delamination of the metal) ,

- Conductivity measurements,

- Testing for material integrity and mechnical fatigue,

- And functional checks,

with the same demonstrators (wherever feasible) being taken through the test sequence cumulatively rather than as isolated coupons.

Testing profiles and acceptance criteria for space are component and mission specific. For the purpose of this campaign, they were derived from the applicable European ECSS standards complemented by the specifications for a shielding housing in a low earth orbit (LEO) mission profile which was provided by an industrial end user. This means testing and validation was independent of the manufacturing method and identical to the way that any similar part would be assessed, whether or not 3D-printed and coated.

This campaign (supported by funding within the ESA SPARK project line) has now shown that metallised polymer components can be qualified for harsh LEO-relevant environments when engineered correctly, while at the same time having generated a reliability dataset that is highly relevant for demanding terrestrial applications in avionics, high-frequency electronics, defence.

Building proof, not promises

As, Horizon Microtechnologiesc CEO Andreas Frölich explains, the intent was not to publish ‘headline results’ in isolation. It was to establish credibility by building a coherent evidence base across the key failure modes that decide whether metal coated, additively manufactured polymers belong in orbit.

“Unlocking the weight and design benefits of metallised polymers for satellites requires proving compatibility with the environmental and operational conditions a component sees across its lifetime,” says Frölich. “That’s exactly what this qualification campaign was designed to do.”

That focus has paid off. Across the core stress tests (outgassing, hot-humidity, mechanical shock (40g), radiation, thermal shock cycling, and atomic oxygen emulation), applied in a largely cumulative sequence, Horizon reports that all metallised demonstrators passed, with no delamination, no detrimental conductivity changes, or other damage observed. Key to this was proper material selection, post-print processing and a bespoke protective coating.

Outgassing: the first major milestone (vacuum compatability)

Horizon’s campaign included outgassing testing conducted to ECSS-Q-ST-70-02C, the European standard used to assess vacuum suitability.

Outgassing matters as a potential material change or degradation pathway and because the release of volatile compounds in vacuum can contaminate the surface of other satellite components, a ‘to-be-avoided’ risk that historically disqualified many polymer-based approaches.

Horizon’s reported results were unambiguous:

- TML (Total Mass Loss): 0.354%

- RML (Recovered Mass Loss): 0.166%

- CVCM (Collected Volatile Condensable Material): 0.000%

These were within ECSS acceptance limits, supporting the conclusion that Horizon’s coated polymer system is compatible with vacuum environments when properly processed and coated.

Humidity and heat: reliability under sustained environmental stress

Next came the 85/85 hot-humid exposure test: Parts were subjected to 85°C at 85% relative humidity for 500 hours. This test is relevant for the ageing of parts while still on earth and is also generally considered to be an accelerated reliability test for coatings. This test was passed.

The implication is straightforward. The passivated metallised surfaces maintained integrity under conditions known to trigger corrosion pathways, moisture ingress issues, and adhesion loss in weaker coating stacks, key for components that must survive handling, ground operations, integration workflows, and potentially demanding terrestrial environments prior to launch, and also for ground-based systems deployed in hot, humid or cycling climates.

Mechanical testing: vibtarion, fatigue and 40G mechanical shock for adhesion confidence

The ability of a component to withstand mechanical stress, especially during launch, is highly dependent on its design. A general qualification of a material (or material+coating system) for suitability with launch conditions therefore cannot be done. Instead, each component must be qualified individually. Data on mechanical materials’ properties is a partial substitute as it can be used for computer simulations of the part behaviour during launch. In practice, however, these properties depend on the printing process parameters and the post processing applied which, in the present case, includes the coating process. The available datasets on 3D printed polymer materials don’t cover this.

To address this gap, Horizon derived a testing coupon for bending tests until failure in the coated state configuration. Identical coupons were also subjected to irradiation (as described below) and then subjected to the same bending tests to determine the ageing behaviour of the part under irradiation. The reasonable target for the number of bending cycles was derived based on launch conditions: assuming a launch phase duration of 300 seconds and up to 100 oscillations per second, a component might see on the order of 30,000 load cycles during launch. Applying a safety factor of ten led to a target of 300,000 cycles that a component should be able to survive before failure. This was achieved.

Finally, Horizon has also included a pragmatic assessment of the demonstrator part as a whole and especially the coating adhesion in a droptower test leading to a mechanical shock/acceleration of 40g. Components such as a shielding housing, would be attached to the rest of the satellite via a metallized surface. Launch would introduce shear loads that directly challenge the interfaces between the coating and its substrates/superstrates (3D printed polymer and the rest of the satellite, respectively). For the test, the coated shielding housing was hence soldered to a dummy PCB which was in turn attached to the platform of the droptower. This way the mechanical shear stress from the acceleration on impact is applied across both interfaces as just described. The test was passed as well. This does not replace a full random-vibration, sine, and shock qualification for components in general. However, it does provide a data point for how (and that) a reference design copes with 40g of acceleration and demonstrates that the polymer-coating adhesion is sufficient.

Together with the collected data on mechanical fatiguing and existing data on mechanical properties this constitutes a good starting point for computer simulations as well as further derisking of specific components during the design phase.

Radiation reristance: surviving the in-orbit dose

Parts in space are exposed to significant radiation with the rate/dose and radiation ‘profile’ depending on the orbit. The radiation doses a satellite in low earth orbit has to survive are typically given as between 3kRad and 50kRad depending on expected life time and orbit height. Horizon’s campaign used irradiation to 100kRad from a Co-60 source for radiation testing. For a specific orbit and mission for which a large set of data was collected and published, this corresponds to the dose accumulated in about four years. There was no specific expected failure mechanisms to the coating itself, but for the novel coating procedure Horizon employs, there also is no reference data. The polymer substrate, on the contrary, was expected to age under irradiation. The degree of that ageing was unknown and neither was its impact on the polymer-metal interface.

The outcome of the coating assessment after irradiation is a clear ‘Pass’, with no degradation of the coating’s adhesion or conductivity detectable.

The polymer substrate response requires nuance: The metallised polymer parts retain shape and can be handled without any apparent need for mechanical precautions but they become more brittle when assessed through the same bending tests described above: Irradiated coupons fail between 3000 and 4000 bending cycles.

That contrast matters. However, peak mechanical loads on the parts occur during launch. Thereafter, in-orbit, the needed mechanical strength is significantly lower depending on the part and its mounting.

Thermal shock: 2,000 cycles from –40°C TO +125°C

To emulate the severe temperature cycling occurring in orbit when satellites transition between the shadow of the earth and irradiation by the sun, Horizon subjected the previously irradiated parts to temperature shock. Specifically, parts where shocked from – 40°C to +125°C within less than 10s and vice versa 2,000 times. The outcome was ‘Pass’.

Thermal cycling is a classic and valid adhesion concern because metal and polymer expand by different amounts, leading to stress build-up in the coating and/or the substrate. Passing this test supports that the metal-polymer interface remains stable, and that conductivity is preserved throughout the cycling history, but it is equally relevant for terrestrial systems exposed to repeated power cycling, outdoor temperature swings, or rapid thermal transients in industrial and automotive environments.

Atomic oxygen resistance (emulation): addressing Leo’s erosive atmoshpere

The atomic oxygen species found in low and very low earth orbits are extremely aggressive and erode many materials. Horizon’s qualification status records an atomic oxygen emulation in air plasma with a total of 183 hours exposure as a ‘Pass’, noting that Kapton erosion (a common reference material for in-orbit atomic oxygen erosion) during the same test corresponded to over 12 months in LEO.

While the test does not fully replicate the in-orbit conditions, its results are still technically and strategically relevant. Thin metallic layers (especially single-digit micron thin ones) cannot afford unanticipated erosion over multi-year missions. In Horizon’s case, the demonstrated AO resistance is achieved as part of a specific coating–passivation layer. Demonstrating the absence of measurable degradation in an AO-relevant stress framework strengthens Horizon’s position for long-duration LEO use cases.

A shift in space hardware possibility

The headline is not just that individual tests were passed in isolation. Instead, the tests replicated, to the extent possible, the cumulative stresses a part would undergo in a low-earth-environment. The absence of coating degradation until the very end underscores the robustness that one would expect from parts used for missions, where failure is not an option and repair is out of the question. The headline hence is that Horizon’s work shows metallised micro-AM can move from ‘interesting prototype’ to credible material system for satellite RF and electronics-adjacent components, validated against the actual stressors that govern acceptance.

Horizon’s approach is explicit. Print in photopolymers and metallise with a highly conductive film only as thick as needed for RF performance (e.g., on the order of multiple skin depths, often ~10 µm copper depending on frequency and conductivity). That’s how the technology yields substantial weight reduction (40% to 80%) and design freedom versus solid metal counterparts, with corresponding launch cost benefits and payload-volume advantages.

In real terms, these results open up new options for:

- RF and microwave components where weight and geometry matter (feed chains, waveguide structures, compact assemblies)

- Shielding housings and precision structures where lightweighting and integration speed offer tangible program advantages and 3D printing can be a cost-effective alternative to CNC machining.

- A broader ‘responsive space’ approach, where shorter turnarounds for payload development and manufacturing are increasingly valued and lead times of a few weeks for established parts are possible

- High-performance terrestrial systems (from advanced radar and 5G/6G front-ends to test and measurement, quantum, and defence electronics) where similar constraints on size, weight, and performance exist, even if the full space environment is not present.

The takeaway

The space industry does not adopt materials because they’re exciting. It adopts them because they’re qualified, characterised, and understood. By treating metallised polymers as a system (and validating the key failure modes that previously undermined confidence) Horizon has built a credible foundation that moves coated micro-AM into a new category. Not speculative, not ‘maybe’, but proven and engineerable for harsh LEO-relevant applications, while also de-risking their use in high-reliability terrestrial domains that share many of the same concerns around temperature, humidity, vibration, and long-term stability.

Horizon has not just passed tests. It has removed several of the key barriers that previously kept coated polymer micro-AM on the sidelines, the lack of qualification data, uncertainty about long-term behaviour of the metal–polymer interface, and the absence of a clearly defined, tested material system that engineers could specify with confidence. At the same time, the company explicitly recognises that system-level mechanical and vibration behaviour, and mission-specific requirements on passivation and contamination control, must still be addressed within each programme’s own qualification campaign. In doing so, the company is driving a shift in how RF and micro-scale space components can be designed, manufactured, and qualified, and is creating a technology platform that can be transferred with confidence into demanding non-space applications as well.

Christian Wolff is Head of Development, Horizon Microtechnologies.

Engineer News Network The ultimate online news and information resource for today’s engineer

Engineer News Network The ultimate online news and information resource for today’s engineer