When looking to 3D print larger fine art sculpture pieces (his own and clients) and specialist elements for the stage and theatre industry, engineering artist and designer Richard Grant decided to take the plunge and build his own. For the x/y gantry, he used the drylin E linear robot from igus.

Since completing a multi-disciplined engineering degree at Brunel, then a postgraduate in 3D printing at Stafford (1996), Richard Grant has been employing advanced technologies for his craft sometimes years in advance of it becoming mainstream.

“I often have to bridge conceptual ideas into technology,” he says, “that’s my niche. I’ve got two very good American-made FDM [Fused Deposition Modelling] printers that have suited me well for a number of years,” says Richard. “With some of the larger structural pieces that I am now being commissioned to create, I was looking for a 3D printer with a larger footprint. Being an engineer, I decided to build my own.”

In the theatre and film industry, the ability to 3D print very large pieces is very attractive. The traditional approach, which is to use a 5-axis milling machine on a very expensive block of polyurethane foam, is slow and highly restrictive. A key benefit to 3D printing over milling is that hollow objects are now possible.

“With the large format 3d printer, I can print anything big – whether it’s a scenic element or a prop,” says Richard. “I have specialist suppliers that can apply composites and tough resins onto my 3D prints, combining the strengths of a 3D print with ultra-tough materials science. Digital design also allows for flexible modelling, iterations, rescaling, symmetry reversal – this is now all very easy.

“In essence, I can design it, build it, spray it, paint it, texture it, film it, use it and smash it – 3D printing is invaluable in my field.”

Clearly, for a 3D printer to work effectively in the film studio or workshop environment all the moving elements need to be resilient to the ingress of dust, dirt and grit.

Traditional metal ball bearings, which require regular lubrication, would draw in particles that, over time, may lead to bearing damage.

Richard had been in talks with igus for a couple of years, since the company’s introduction of its iglidur tribo-filament for printing wear resistant parts.

“I was interested in using the material to print replacement runners for one on my printers,” he recalls. “My main contact at igus is Adam Sanjurgo – he’s my ‘go to’ person to answer all questions relating to igus’ engineering plastics and linear automation systems.”

Wanting to push the limits of 3D printing, igus was keen to invest in a developer’s project by providing the correct linear system available within the igus range.

“The benefit for igus is that we can examine the performance data of the system,” explains Adam. “Gathering real-world data in this unique large 3D printer application is invaluable to us.”

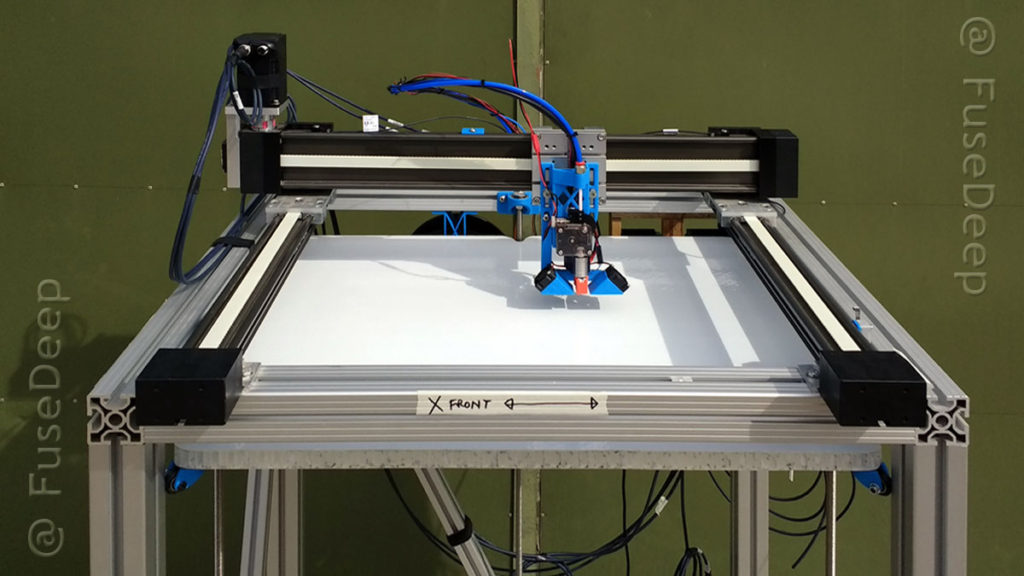

Having already made a start with the metalwork for the printer, the complimentary igus drylin W linear system proved to be a great benefit towards the realisation of Richard’s project.

The system comes, as standard, with an x-y workspace of 500 x 500mm and a short 100mm pick-up. He removed the vertical axis and created a large frame with homemade (3D printed) parts to achieve a print area of approximately 450 x 450 x 1600 mm.

Richard said: “There is no doubt, the igus gantry is incredibly engineered and a rock solid start point for this application”

Another key benefit of using the drylin W linear system is that all its bearing elements are made of a special engineering plastic as opposed to conventional ball bearings. This tribopolymer material contains solid lubricants, embedded as minute particles in its homogenous structure.

During operation, the material releases tiny amounts of lubricant across the wear surface to automatically lubricate the bearings and prevent friction in the system; this negates the need for regular lubrication and maintenance, and, ultimately, eliminates the risk of dust particles causing damage to the bearings.

Engineer News Network The ultimate online news and information resource for today’s engineer

Engineer News Network The ultimate online news and information resource for today’s engineer