After losing most of its European gas market share, Russia has been forced to rethink its export strategy. With China’s major expansion projects slow to materialise, Moscow is increasingly looking closer to home – from Central Asia to Turkey – in an effort to reroute volumes it can no longer sell westward. Aura Sabadus examines how pricing, infrastructure constraints and geopolitical pressures are shaping outcomes across this strategically critical region. She explores negotiations with Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, which together could take in around 20bcm per year in the upcoming years, the feasibility of north–south corridors via Iran and Azerbaijan, and the growing importance of Turkey as both a key buyer and an emerging regional gas hub

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and subsequent curtailment of gas exports to EU markets sent shockwaves across Europe, forcing buyers to find alternative solutions and adapt to a new reality.

To compensate for the loss of the European market, Russia pivoted east, hoping to entice China with new or expanded big-ticket gas projects, which might enable Gazprom to export 100 billion cubic metres (bcm)/year if plans materialise in the future.

In between Europe and China, however, there is the resource-rich Eurasian landmass, where oil and gas supplies often follow the ebbs and flow of geopolitical shifts and where Russia has been seeking lately to rebuild its influence and reroute some of the volumes it cannot sell to Europe.

ICIS has found that Gazprom has been in talks to sell at least 75bcm/year of gas, but Moscow’s hopes for new markets and shipping routes have been clashing with buyers’ demands for fair prices and flexibility or proud ambitions of their own to expand regionally.

Over the past three years, the Russian gas producer has been in talks with Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan to facilitate gas transit to China or to increase gas exports to their markets. Regional observers told ICIS the two countries could off-take an additional 20bcm/year in the upcoming years as they are either planning to switch from coal to gas for power generation or need to compensate for naturally depleting reserves.

While the two countries are pragmatic in their approach, they are also taking a cautious view.

“For most regional governments, it’s not about alignment, it’s about keeping options open,” Shohruh Zukhritdinov, a regional energy expert, told ICIS. “The old Soviet grid is still there, and if it can be used to balance domestic demand or strengthen negotiating power with Beijing or Ankara, they’ll take it,” he added.

Iran is another target for Russia

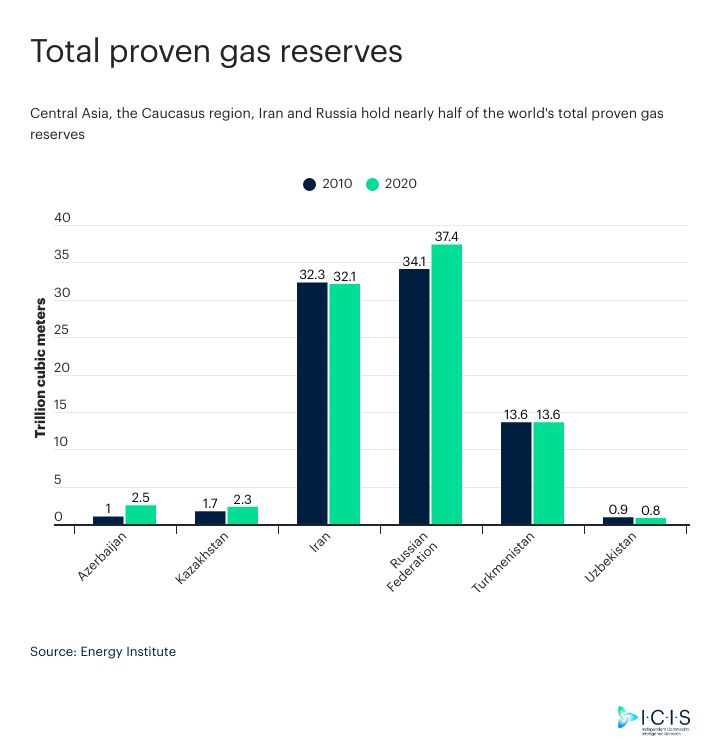

Although sitting on the world’s second largest gas reserves, years of sanctions have left it unable to develop domestic production and infrastructure. This meant it had to rely increasingly on gas swaps with Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan to meet peak demand in summer or winter.

Sensing Iran’s troubles, Russia now wants to build a north-south corridor, with Russian President Vladimir Putin stating that the project could provide as much as 55bcm/year if issues related to pricing and infrastructure are agreed on.

Nevertheless, an initial arrangement agreed in April for the supply of 1.8bcm/year using neighbouring Azerbaijan’s infrastructure seems to have reached a dead end, with parties failing to strike a compromise on prices, at least for now.

Russia has also sought to use Azerbaijan as a bridgehead to other markets both regionally and in Europe, but the Caspian producer proved nimbler, locking in new clients often at the expense of Russia.

In 2024, the two countries were discussing a complex swap scheme to facilitate the extension

of Russian gas transit to Europe via Ukraine under an Azeri label.

The plan fell through. Azerbaijan and Russia reportedly failed to reach an agreement on price and the scheme itself proved unconvincing for Kyiv.

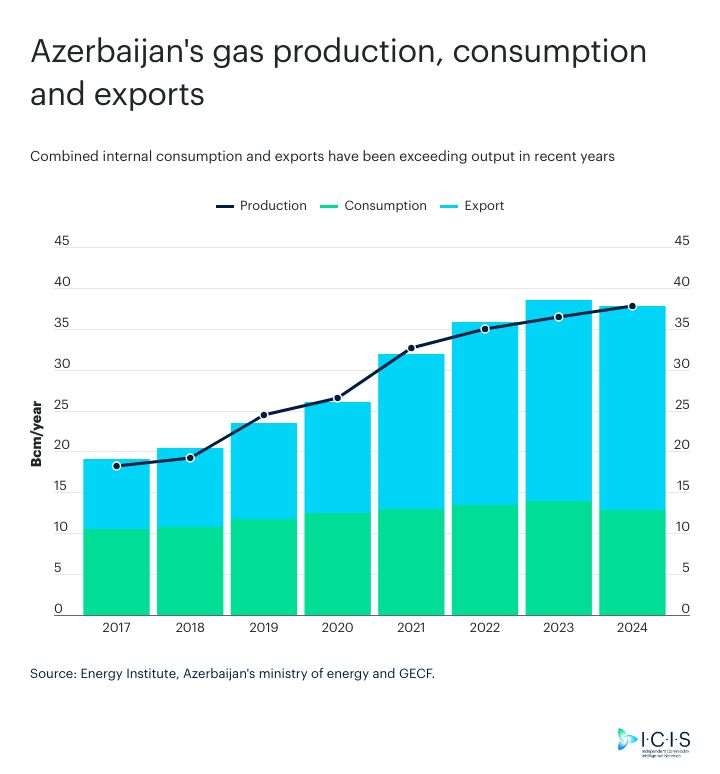

ICIS accepts no liability for commercial decisions based on the content of this report. But while Russia’s hopes to recapture its European market share are diminishing as the EU is planning to ban gas imports from 2027, Azerbaijan is expecting to almost double its exports to the bloc by the end of the decade.

Turkey

It did the same in Turkey, where it has also consolidated its foothold, offering flexibility of price and volume, which Ankara is now seeking to replicate in negotiations with Russia for the renewal of two expiring supply contracts.

Historically, Turkey has been one of Russia’s most valuable markets, thanks to its size and geographical position.

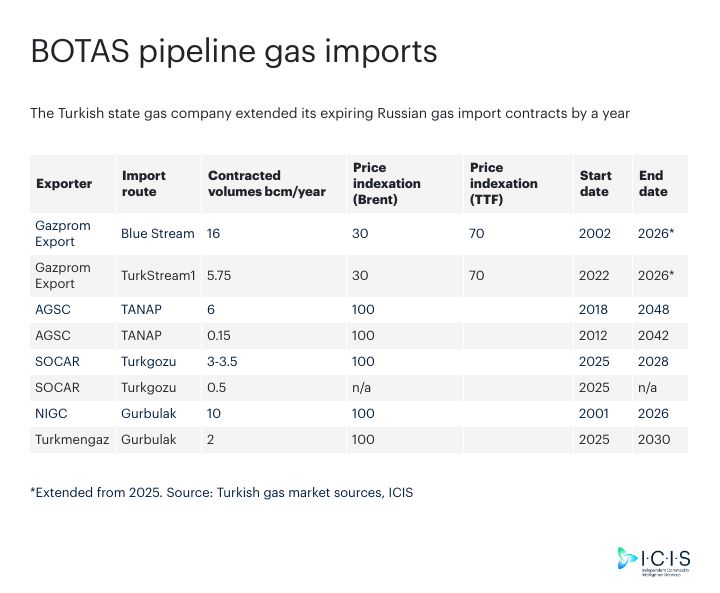

At the beginning of December, Ankara said it had extended its expiring Russian long-term import contracts totalling 21bcm/year by another year.

Meanwhile, its Iranian 10bcm/year supply agreement is also due to end in September 2026.

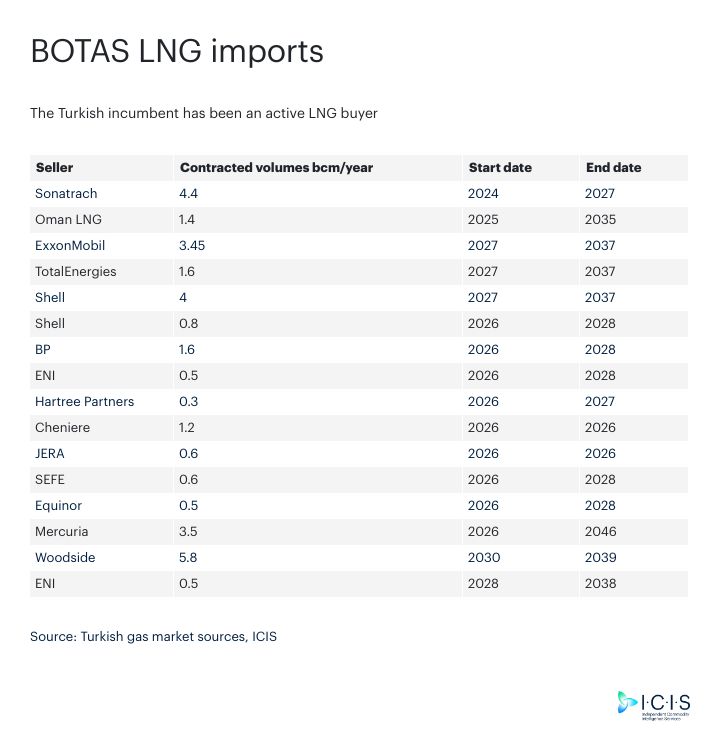

The question is what will happen from 2027 onwards, particularly now that Turkey has expanded its LNG regasification capacity and has been signing a flurry of supply deals with global producers, primarily from the US?

While Russia’s ability to provide supply and pricing flexibility will determine the extent to which it will be able to secure its position regionally, it would be a mistake to assume that pragmatism alone will shape relations from Kazakhstan to Turkey.

ICIS has analysed supply patterns in Central Asia, the Caspian region and Turkey to understand how energy and political pursuits are converging and how these networks of interest may ultimately impact global gas markets.

The picture that emerges is that the Eurasian landmass is both a battleground of competing interests and a vast expanse of land connecting resources and shifting loyalties as explained by this ICIS whitepaper.

Central Asian Buyers

Since the loss of its European market share, Russia has been in talks to sell more gas to central Asian countries, but the question is whether its outreach was opportunistic or a solid offer for long-term co-operation?

In the 1970s the USSR initiated the construction of the central Asia gas trunklines with a view to import gas from Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan via Kazakh territory and the Caucasus.

At the time, Kazakhstan was seen as a transit country, which meant that the infrastructure was designed to reflect that role but ultimately created major imbalances. The western and northern regions have access to gas while the more industrialized southeastern part had to rely on imports from Uzbekistan.

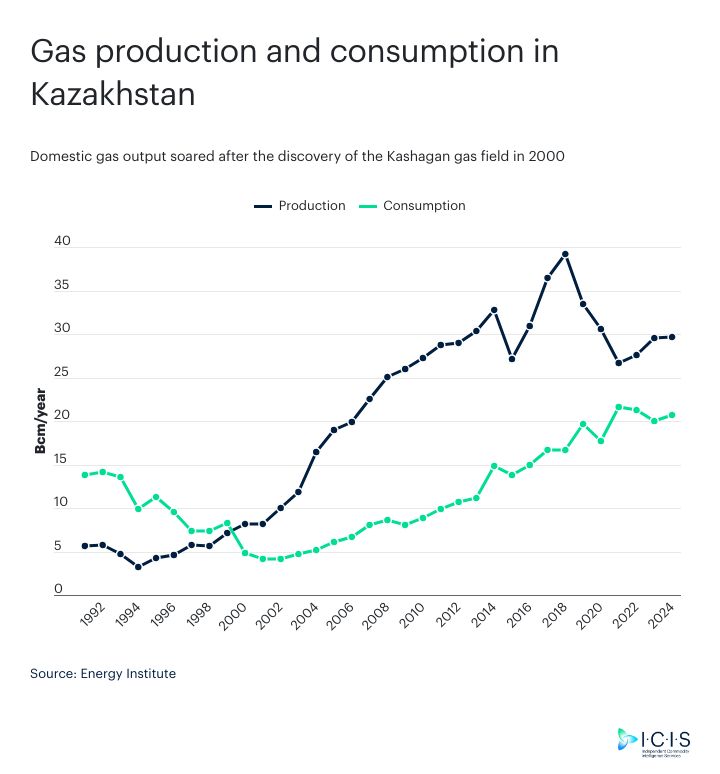

Following the breakup of the Soviet Union, regional countries began to reorganise their gas industry and find new customers. In Kazakhstan’s case the discovery of the giant Kashagan field in 2000 changed the rules of the game, as the country became a producer and exporter itself.

Fast forward to 2023, state company QazaqGaz signed a 4.5-5bcm/year supply deal with PetroChina until 2026 and said it boosted volumes in 2025.

However, Kazakhstan faces winter demand constraints and has been importing Russian

volumes during the cold months, off-taking around 0.5bcm/year in 2023 before ramping up

to 3.8bcm/year in 2024, according to figures quoted by local media.

Gazprom said in September 2025 it had reached an agreement with QazaqGaz to increase supplies to Kazakhstan for this year and 2026. However, the latter played down the claims, noting merely that the two parties had discussed potential bilateral cooperation related togas supplies, transit, processing and the expansion of infrastructure.

A month later, the two countries said they had reached a decision for the construction of transit pipeline to China, which could also include deliveries to the northeastern provinces of Kazakhstan.

Zukhritdinov, however, noted that progress would depend less on politics and more on tariffs, swap formulas and transparency.

“If those are solid, the corridor might quietly work in the background; if not, it’ll stay a press statement,” he explained.

Domestic demand

Although Kazakhstan’s annual gas demand hovers around 20bcm/year, it cannot satisfy it from its domestic production as half of produced volumes need to be reinjected in oil wells to maintain reservoir pressure, according to Ilham Shaban, a Caspian oil and gas analyst based in Baku.

Furthermore, Kazakhstan lacks its own large gas processing plant and is forced to ship gas extracted from the Karachaganak field to Russia (Orenburg) for purification and then import its own gas in smaller quantities.

Even a gas supply arrangement by Italy’s Eni with Gazprom to sell Kazakh gas from its Karachaganak nnonshore field to Turkey involved the transport of gas to Orenburg where it had to be processed.

The gas that was shipped further to Turkey via Blue Stream may have been swapped Russian gas. However, Eni decided to pull out of the deal in 2025, just months before its expiry at the end of this year.

In the longer term, Kazakhstan’s gas demand is set to increase largely thanks to coal-to-gas switching. The country generates 70% of its electricity from coal but plans to reduce coal consumption in the energy sector over the next 10 years. Moreover, the government intends to increase the gasification rate of the country from 62% to 80% in the mid-term.

Kazakhstan had been discussing potential imports of 10bcm/year of Russian gas for many years, but so far it failed to reach an agreement related to price.

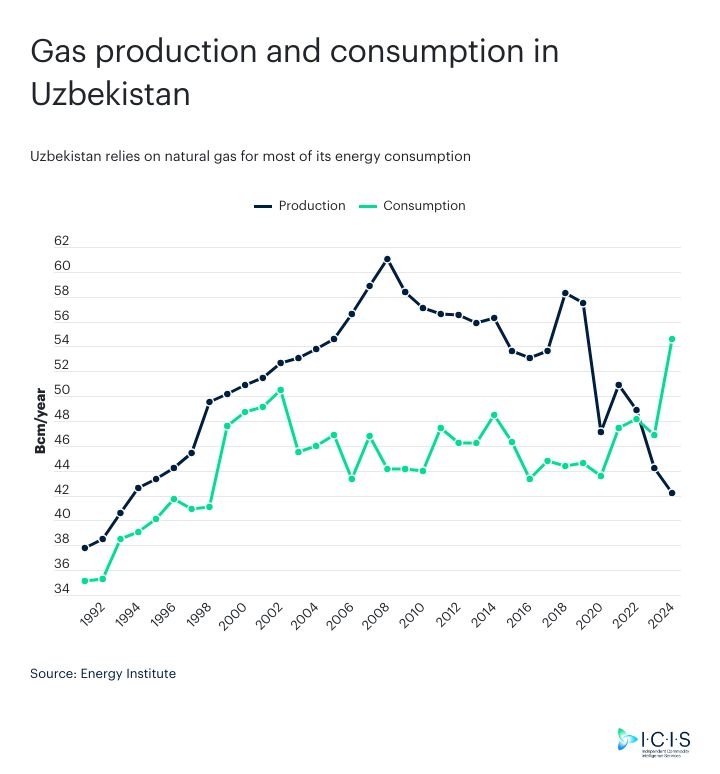

On the other hand, neighbouring Uzbekistan became a net importer of gas in 2023, and import volumes are expected to grow to 11 billion cubic meters, according to Shaban.

Ten years ago, it was producing over 60bcm of natural gas, but marketable output was 44.6bcm/year in 2024 and is expected to fall further. In contrast its gas demand stands above 50bcm/year as gas covers 80% of its total energy consumption.

To plug the deficit, it agreed to import Russian gas in 2023, securing 2.8bcm/year initially but expecting to increase offtakes to 11bcm/year by 2030.

Shaban says both countries could import a combined 20bcm/year of Russian gas by the end of the decade.

Alternatives

Although there is admittedly a pressing need to secure additional imports to meet demand, Zukhritdinov said countries were keeping their options open and since the old Soviet grid was there it might as well be used to balance domestic demand.

For now, however, their options are limited. The only alternative regional producer, Turkmenistan, is dependent on China for the development of its gas industry.

Sitting on over 14 trillion cubic meters of gas, it exports annually around 30bcm to China and indicated an intention to double exports in the longer-term.

More recently, it had agreed to ship gas to Turkey via swaps with Iran, but volumes are limited and Turkey does not represent a real alternative market, at least for the time being.

“Turkmen gas is practically not consumed by other [regional] countries,” said Shaban. “This is due to China’s specific policy, which financed Turkmen gas production and created the gas export infrastructure from central Asia. Therefore, it dictated its terms. Turkmenistan is completely dependent on China for the development of its gas industry.”

Rich but (energy) poor

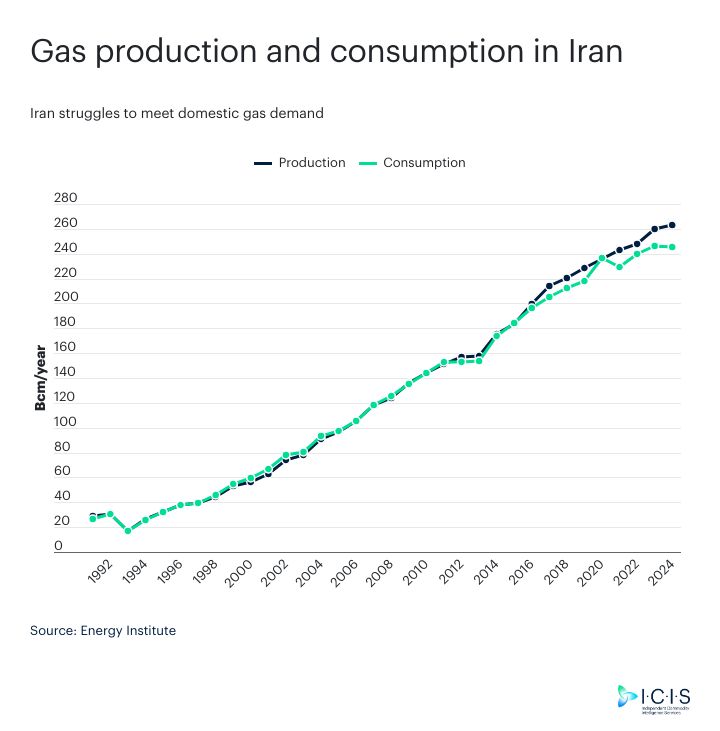

Although holding the world’s second largest gas reserves, Iran has been struggling to meet even domestic demand lately.

Three years ago, it faced difficulties supplying gas to consumers not only in winter but also in summer.

Iran produces around 260bcm annually, but exports are less than 20bcm/year and the rest is consumed domestically.

When accounting for exports, the gap between supply and demand is expected to widen amid increased consumption in the residential and power generation sector projected to continue through to 2040.

Domestic consumption

Severe international sanctions have restricted the development of its infrastructure, which means that Iran had been relying on imports from neighboring Turkmenistan to meet demand, particularly in the northern part of the country.

Since 2022, it has been discussing possible imports of natural gas from Russia. In 2024, the National Iranian Gas Company (NIGC) signed a memorandum of understanding with Gazprom on the supply of Russian pipeline gas to Iran, but no details related to volume, price or route were disclosed.

Shaban noted that earlier this year, during the visit of Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian to Moscow, a 20-year strategic agreement between Russia and Iran was signed, which included provisions on energy and joint gas projects. The Russian parliament later ratified this document in April 2025.

Russia’s president Vladimir Putin said the project could provide up to 55bcm/year to Iran if technical, pricing and infrastructure issues are agreed upon.

However, Shaban points out that an initial project of 1.8bcm/year for supplies in September via Azerbaijan fell flat as counterparties had not agreed on prices, while Azerbaijani officials insisted they had not received any proposals from Moscow regarding the transit of Russian gas to Iran.

Azerbaijan has the technical capacity to transit Russian gas to Iran.

“The existing gas infrastructure between Russia and Azerbaijan: the Mozdok (North Caucasus) – Hajigabul (Azerbaijan) pipeline was built in 1982. At that time, this pipeline had a capacity of 10bcm/year; currently, it can transport no more than 5bcm of gas because of deteriorating technical condition as it wasn’t in operation from 1991 to 2001.”

From Hajigabul there is an extension to Astara, in northern Iran, but its capacity is limited to 2bcm/year. To expand it, Iran would need to build a new gas compressor station to increase the pumping capacity to 5bcm/year.

For volumes higher than 5bcm/year, the three countries would need to build additional infrastructure, which would require signing intergovernmental and commercial agreements.

“Given the current political situation, with both Russia and Iran under sanctions, this seems unlikely,” Shaban says.

He added that Azerbaijan is keen to observe the ‘rules of the game’, co-operating closely with the EU and the US for the past 30 years and recognising Ukraine’s territorial integrity, assisting Kyiv with energy resources and technical equipment.

‘Smart games’

Zukhritdinov believes Azerbaijan is playing a ‘smart game’, positioning itself as a bridge +rather than a battleground, opting to connect systems over choosing sides.

If that is the case, the success of a north-south corridor for Russian gas supplies to Iran via

Azerbaijan may be determined more by price than politics.

This may have been partially the case in 2024 when Russia and Azerbaijan were reportedly in talks for a complex gas swap scheme for the continuation of gas transit via Ukraine. The scheme fell through amid reports parties could not agree on price.

However, there was also political pressure from the Ukrainian public, which was concerned that the gas transiting Ukraine would be of Russian origin. Their concerns were backed up by figures.

In recent years, Azerbaijan’s gas consumption and exports have been overshooting production, which meant that the country had to import around 1bcm/year of Russian gas to meet winter demand.

Given these circumstances, Azerbaijan could not have replaced around 15bcm/year of Russian transit gas via Ukraine from its own domestic production.

Nevertheless, Azerbaijan has been keen to cultivate its European market, supplying gas via the Southern Gas Corridor to buyers in Greece, Bulgaria and Italy since 2020 and seeking to increase spot volumes through short-term supplies to buyers in Hungary, Serbia, Romania, among others.

As of 2025, more than half of Azerbaijani gas is delivered to Europe and Baku plans to increase gas exports by 8bcm/year 2030 as it develops phase three of the Shah Deniz project, which supplies the Southern Gas Corridor.

There are also plans to expand the Absheron field and explore new reserves in the Umid-Babek gas complex in the South Caspian Sea.

“In five years, Europe may not have any Russian gas, but Azerbaijani gas volumes will be at

least 20 billion cubic meters,” said Shaban.

Officially, he says, Azerbaijan positions itself as the crossroad of east-west and north-south

routes, facilitating regional cooperation.

Unofficially, it remains in fierce competition with neighboring countries and this is best reflected in its market strategy in neighboring Turkey, as explained in part four of this ICIS series.

Competition or co-operation

Azerbaijani officials generally avoid using the term ‘competing with Russia or Iran’ in their

public statements, Ilham Shaban, a Caspian oil and gas analyst from Baku told ICIS.

“We often declare our desire for cooperation. Thanks to trade and developing co-operation,

Azerbaijan has proven that, [although] located between Russia and Iran, both global giants in

terms of oil and gas reserves, it could not only bring energy resources to global markets but

also build its oil and gas [export] pipelines, bypassing them.”

Azerbaijan could not have achieved its objectives without Turkey, which facilitated the construction of the Trans-Anatolian Pipeline (TANAP), helping to bring gas to southern Europe and of the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) which brings oil to global markets.

Shaban notes that for the past seven years, Azerbaijan has been selling more gas on foreign markets than Iran and, since 2007, it displaced Russia to become the main seller of gas to Georgia, exporting between 1.1bcm/year to 1.4bcm/year.

In Turkey, it started to chip away at Russia’s market share, which fell from more than 50% of the country’s total imports in 2014 to around 41% last year. In contrast, Azerbaijan’s exports nearly doubled to 11.5bcm/year in 2024 from 6bcm/year in 2014 as the country offered cheaper prices and more flexibility.

Turkey gas imports

The new year 2026 will be a pivotal year for the Turkish gas market.

At the beginning of December, Russia agreed to extend two expiring long-term supply contracts by another year while Turkey’s Iranian long-term supply agreement is also due to end in September 2026.

Several sources told ICIS that the expiring contracts included a clause which offered the option to extend the terms for a limited period of time.

By the end of next year Turkey will have to decide whether it intends to continue buying Russian and Iranian gas and if so under what terms.

Many Turkish market sources told ICIS that Turkey will renew the Russian contracts because gas imported from Blue Stream and TurkStream1 is necessary to keep a balanced pressure in the system.

However, they point out that the real uncertainty is about quantities and price as Turkey has been reportedly asking Gazprom to change the hybrid price formula by reducing the share of the TTF hub indexation and increasing that of oil.

The information cannot be confirmed, but Turkey is in a significantly better position to negotiate a discount because Gazprom is strapped for alternative markets and gas prices are on a downward trend.

Less certain is the fate of Iranian gas supplies to Turkey, historically, the most expensive of all imported gas resources. Nominally, Turkey’s long-term contract stipulates 10bcm of supplies annually. In practice, however, offtakes have been lower, not least because Iran had difficulties in honoring contractual terms.

The question that arises is who will be taking up Iran’s Turkish market share if the contract is

not renewed.

There are a number of contenders including Turkmenistan, which had been in talks to export more gas to Turkey, Russia or global LNG producers.

Export ambitions

Turkey has ambitions of its own to become a regional exporter after it discovered gas resources in its Black Sea exclusive economic zone and is expecting to double its daily gas production by 2026 and quadruple it from 2028. Daily gas output currently hovers around 9.5 million cubic metres.

BOTAS has signed numerous LNG contracts, most of which allow the rerouting of supplies to other markets and said it would be interested in investing in the US gas market.

Turkish market sources say BOTAS’ combined portfolio of domestic and imported gas would easily outpace demand in the upcoming years, which means the state supplier would be in a position to expand its outreach and compete with Russia and Azerbaijan in Europe.

However, as long as Turkey continues to offtake Russian gas, there will always be suspicions about exports reaching Europe from this market.

One option would be for BOTAS to transfer Russian imports to the private sector and limit BOTAS’ portfolio to its domestic production plus its Azeri and LNG imports.

While this might be an option, the government is unlikely to relinquish a major instrument of power, which had earned Turkish bureaucrats a chair at the high table of geopolitical bargaining.

Not an easy task

Historically, the vast tract of land stretching from China to the Mediterranean has been a source of fascination, prompting observers to describe it either as a ‘Great Game’ battleground for competing interests or a Silk Road for traders in search of riches. In reality, it is both.

Gazprom’s loss of the European gas market in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has forced it to seek buyers in the east. But just like in China, where it is struggling to advance its 50bcm/year Power of Siberia 2 project, it is also finding it difficult to recapture its central Asian hinterland.

Regional producers Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan are caught between a rock and a hard place. Both need more imports to meet domestic demand but know that this may come with increased political attachments or could jeopardize plans to develop their own gas sectors.

Limited options

Despite signing a 20-year comprehensive strategic partnership treaty which became effective

in October 2025 and covers defense, especially drone technology, nuclear energy, gas pipelines and finance, Iran finds itself in a tough spot.

Both countries are under international sanctions, but unlike Russia, which has options to monetise gas resources, Iran has no choices left.

The expiry of its long-term supply contract to Turkey in 2026 could put an end to its export revenues just as it struggles to develop its own resources.

Right now, it faces the prospect of becoming reliant on Russian or Turkmen gas despite holding the world’s second largest gas reserves.

If Turkey were to cancel the Iranian contract, the obvious question is who will take up its market share?

Russia had historically supplied around half of Turkey’s imports. However, Azerbaijan has dented its market share in recent years, offering cheaper prices and flexibility.

Turkey trump cards

Having lost most of its European market share, Russia is in a much weaker negotiating position

than Turkey. But Turkey also needs Russian gas for technical reasons even though it has allegedly come under pressure from the US to relinquish its Russian imports.

With a surge in global LNG production expected in the upcoming years and sluggish demand

worldwide, it is obvious that global and regional producers will be competing to gain access

to Turkey, a prized market thanks to its size and geographical position.

What is less obvious is that Turkey is now equipped to become an exporter in its own right.

Aura Sabadus is Senior Editor at Independent Commodity Intelligence Services (ICIS), a global energy and petrochemicals news and market data publisher. ICIS accepts no liability for commercial decisions based on the content of this report.

Engineer News Network The ultimate online news and information resource for today’s engineer

Engineer News Network The ultimate online news and information resource for today’s engineer