Brian Durant highlights how smart, operator-focused automation in bulk material handling boosts throughput, reduces downtime, and improves safety by integrating many machines into a coordinated control system. Instead of ripping and replacing legacy equipment, it advocates tactical modernization that bridges old and new assets, standardises alarms, and improves visibility. The result is steadier, more reliable production and calmer plant operations driven by practical, well-engineered controls

Across bulk material handling, controls and automation have become the quiet engine of competitiveness. When these automated systems are thoughtfully engineered, plants see measurable gains, including higher throughput, fewer unplanned stops, safer operation, and clearer decision making at every level, from the operator panel to the enterprise layer. The day-to-day reality is less glamorous but more important: moving powders, granules, and ingredients consistently while meeting production targets and regulatory expectations. Purpose-built control systems make that consistency repeatable by coordinating equipment, sequencing steps, validating interlocks, and surfacing the right information to the right person at the right time.

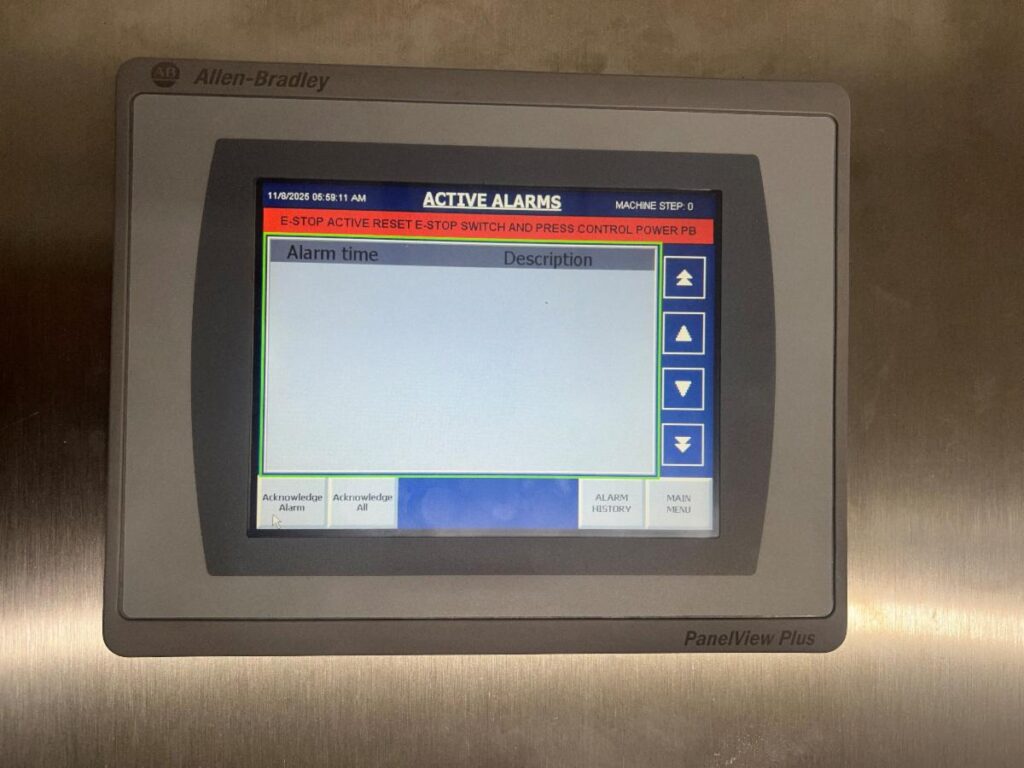

A big part of ‘smart’ systems is practical visibility. Systems that identify the specific fault location, prompt operators with what to check, and notify the line when materials are running low prevent small issues from cascading into hours of downtime. Those heads-up cues, such as letting staff know it’s time to stage the next tote or replenish a bin, keep the process balanced, which is often the difference between sprint-and-stall production and steady, profitable flow.

The integration imperative: one brain for many machines

The defining trend in material handling controls is the shift from machine-centric islands to line-centric orchestration. Facilities want a single control package that can supervise not only conveying, but also upstream and downstream assets, mixers, feeders, packaging cells, from multiple OEMs. This requires panels and software that speak the languages of the plant: DCS connections, third-party PLCs, and a mix of industrial communication protocols. In short, one brain coordinating many limbs.

Done well, that orchestration fades into the background for operators. Instead of babysitting handoffs, they get a unified interface that sequences steps, enforces permissives, and makes line status obvious at a glance. Consider projects where the conveying system sits mid-process: integrating the machine before, the conveyor itself, and the machine after into a single control package removes manual interventions and error-prone timing. In practice, this compresses troubleshooting time (the HMI points to the faulted segment), prevents misfeeds, and keeps OEE steadier across shifts.

Integration also means acknowledging the brownfield reality. Most plants run a patchwork of vintage machines and vendors. Modernising tactically, bridging old to new rather than ripping and replacing, starts with a discovery deep-dive into the current state (I/O, protocols, safety functions, documentation), then a design that slots in easily without breaking what already works. The most effective deployments use customized interfaces and gateway strategies so legacy controls can “talk” to the new system and the new system can safely coordinate the legacy asset.

From legacy bottlenecks to plant-wide reliability

Common roadblocks show up repeatedly in the form of antiquated controls that cannot communicate, undocumented changes layered over time, and compliance demands that differ by area (sanitary zones vs. hazardous locations). The path forward from here is systematic: map the process, rationalize setpoints and states, standardize alarms, and design for the most constrained environment first (e.g., dust-hazardous areas or washdown requirements). For powders in particular, panels and devices must meet the correct classification, or the reliability you gain on paper never materializes on the floor.

This is where the choice of a controls partner matters less for branding and more for engineering depth. Manufacturers that design and build their panels in-house maintain tighter quality control and verification. Every panel can be function-tested against the intended process before shipment, which reduces commissioning surprises and accelerates time to rate. In practice, that looks like simulated I/O, recipe validation, and fault-tree checks in a shop environment, so day one on site is about turning product, not wiring triage.

Around this point in a project, many teams look for a provider with both equipment and controls pedigree, someone who understands powders, conveying physics, and the realities of regulated environments. Hapman, a global leader in custom bulk material handling equipment, is one example of why domain experience matters. With decades of work across industries like food and beverage, pharmaceuticals, chemicals, agriculture, plastics, and wastewater, Hapman has developed control designs that anticipate edge cases and integrate smoothly with the rest of the plant. Experience across thousands of applications goes beyond informing just hardware, and extends to informing how interlocks and operator flows are structured, so the line keeps running under real-world conditions.

Design for operators first: fault clarity, event foresight and safer flow

Robust automation improves reliability, and operator-centered automation keeps a system reliable. Intuitive HMIs that name the faulted device or zone cut troubleshooting from minutes to moments. Clear alarm philosophy, prioritised, actionable, and free of nuisance, prevents alarm floods that operators learn to ignore. Additionally, proactive notifications (“Load material in feeder B now to avoid a stop in 12 minutes”) turn firefighting into simple prep work. Plants that institutionalize these patterns see fewer micro-stops and faster shift changeovers because system status is clear and accessible, rather than relying on informal or hard-to-transfer knowledge.

Compatibility is the other pillar of operator-first design. Control platforms should natively support common DCS connections and the PLC families already present, so upgrades don’t force wholesale migrations. In mixed-vintage environments, that often means adding communication modules or protocol gateways and then validating handshakes thoroughly, start/stop, permissives, speed references, feedbacks, and alarms, before the first production run. Case work shows how unifying three separate process steps into one control package eliminates handoff gaps and reduces manual confirmations, which is especially valuable when staffing is lean.

Finally, industry context cannot be bolted on at the end. The food and beverage and pharmaceutical industry bring sanitary and documentation requirements, chemicals bring area classification and containment concerns, and agriculture and building products bring dust management and ruggedisation needs. Controls that ‘meet or exceed’ the relevant standards, rather than merely connect, avoid expensive rework and compliance findings later.

How to move forward: a practical playbook for upgrades

Modernisation does not need to be a major overhaul. Start by conducting an inventory of devices, mapping states and transitions, documenting possible failures, and ranking risks by consequence and likelihood. Use this data to define what needs to be integrated immediately to protect throughput and safety, and identify what can wait for later stages. Building in diagnostics and material prompts from the start saves lost production time down the road. When choosing a partner, give preference to those who engineer and test panels internally, demonstrate clear handoffs to your current control systems, and prove the ability to integrate upstream and downstream assets.

The payout is not just better OEE; it is calmer operations. When controls remove ambiguity by clarifying where to look, what to do, and when to load, the plant runs at a steady cadence and onboarding becomes easier. The result is a line that behaves the same way on Tuesday night as it did on Monday morning. This is the quiet definition of reliability.

Brian Durant is Electrical Controls Engineering Manager at Hapman.

Engineer News Network The ultimate online news and information resource for today’s engineer

Engineer News Network The ultimate online news and information resource for today’s engineer